Hello, Night Hag readers! Happy almost September — happy almost Spooky Season! In September I’ll be back in your inboxes with Spooky Season content, but this week: what have I been doing since you last heard from me?

I spent most of the summer reconsidering a genre that, historically, I haven’t much liked: science fiction. I read several of the internet’s favorite sci-fi novels, I watched a few Villeneuve films, and I tried to follow along as Leonard Susskind talked about physics.1

So here is an essay that no one asked for, in which I consider why I disliked science fiction to begin with and what I think about it now. Is this a niche topic for an audience of one? I hope not, but I guess we’ll find out!

(To see what I read and what I recommend, skip to the bottom.)

Science fiction & me: a troubled past

As a kid, I didn’t like sci-fi, though I’m not sure I could have told you why. Maybe I thought it was “too weird,” or had a whiff of the uncool about it, or maybe its imagined futures just made me too uncomfortable.

As young adult, I still didn’t like sci-fi. I walked around saying things like “sci-fi requires too much world-building,” and “I don’t want to learn a whole new vocabulary just to read a book.”

More recently, I thought sci-fi was too rational, too empirical, too scientific.2 Impressed with my own tolerance for uncertainty, I might have said that I preferred the mysterious, irrational world of the Gothic to the over-explained, empirical world of science fiction.3

After this summer, I now understand that sci-fi is not all rational, empirical, and scientific. In fact, much of it is quite silly, as I discovered when I read The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (basically Monty Python in space) and watched the new season of Doctor Who (“silly” doesn’t do justice to the ridiculousness of some episodes).

But despite having reconsidered many of my previous assumptions, I still have this feeling that science fiction has too much Enlightenment and not enough enchantment for my taste. How can that be in a genre that is (often but not always) literally about hanging out with aliens? Let’s investigate.

What is sci-fi?

When defining science fiction for my students, I would have said it’s a genre that takes known scientific principles and extrapolates them to an imagined future. In other words, sci-fi is distinct from fantasy because it is, at least in theory, possible.

But Ursula K. Le Guin doesn’t agree. She says:

Fortunately, though extrapolation is an element of science fiction, it isn’t the name of the game by any means. [Extrapolation] is far too rationalist and simplistic to satisfy the imaginative mind, whether the writer’s or the reader’s.4

Okay fine. I guess I have to reconsider. Maybe science fiction isn’t strictly extrapolative. Maybe it isn’t limited by an obsession with rationality. Maybe the Gothic and science fiction have more in common than I originally thought?

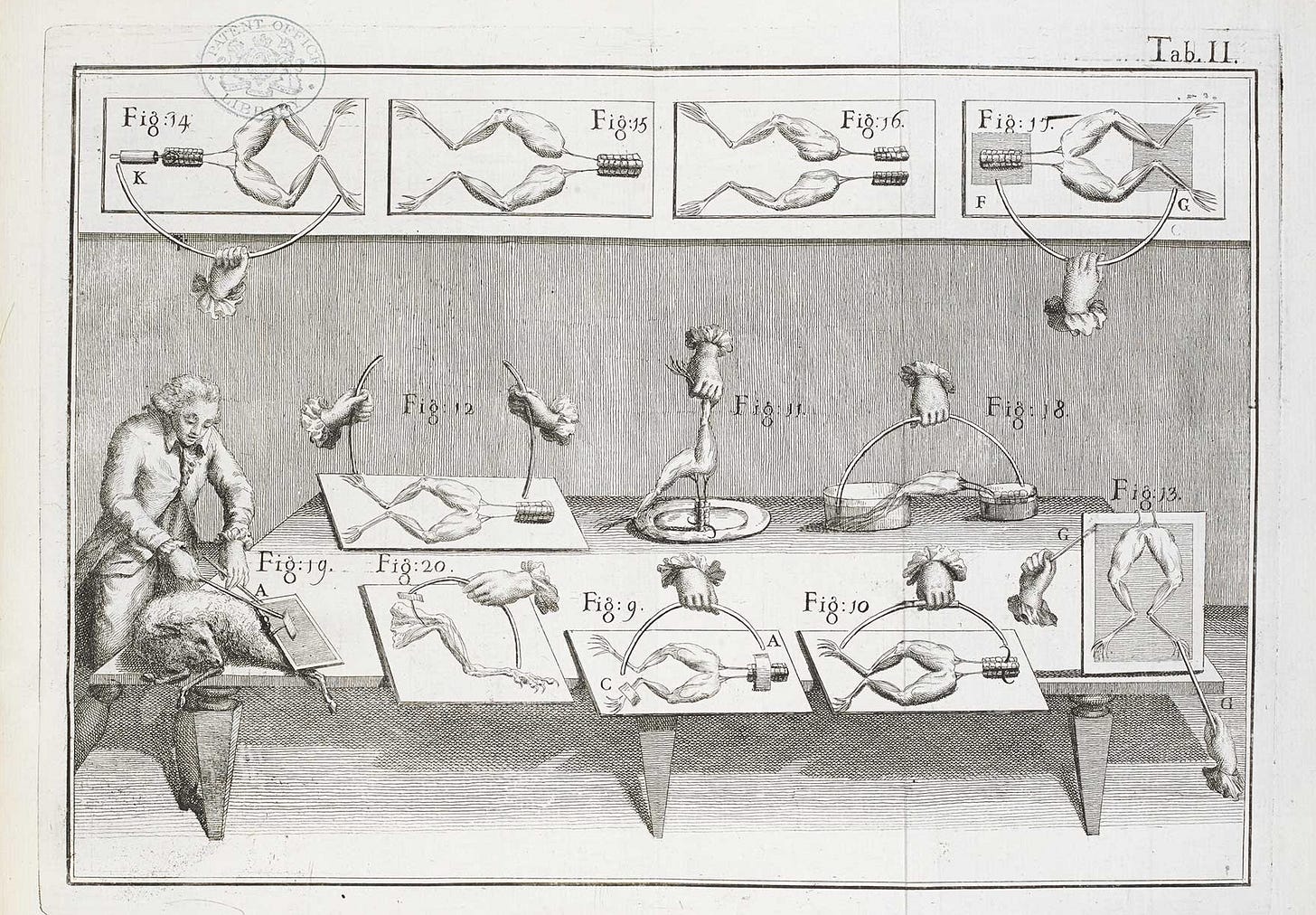

Evidently Mary Shelley thought so. She wouldn’t have been thinking of science fiction as a genre in 1816, but she clearly believed that the scientific qualities of Frankenstein were compatible with the Gothic. Frankenstein imagines the consequences of Galvanism, the 18th-century discovery that you can use electric current to make muscles twitch (in Galvani’s case, dead frogs’ legs). In Frankenstein, Shelley asks (I’m paraphrasing), “what if you could use electricity to fully reanimate dead tissue, creating new life?”.5 Et voila! Science fiction is born.6

Frankenstein allows the supernatural and the scientific to co-exist; but despite Victor’s God-like powers, nature ultimately asserts its dominance in Frankenstein, with (spoiler alert) Victor and the Creature both succumbing to the sublime power of the Arctic. (An easily forgettable, but crucial, part of the story is that it begins and ends with a doomed Arctic expedition.)

Like Frankenstein, much science fiction takes place in a vast expanse hostile to human life (the universe — maybe you’ve heard of it?). But unlike Frankenstein, where nature triumphs in the end, almost everything I read this summer shows humans (or aliens) dominating the natural world, overcoming natural limits through technological advancement.

To be sure, some science fiction highlights the disastrous consequences of this domination, and in that way sci-fi seems to share a project with the Gothic: critique of Enlightenment thinking.7 But while the Gothic tends to foreground the unknown, unseen forces beyond human understanding, in sci-fi almost everything feels known or, at least, knowable.

After all of the dominating, overcoming, and knowing of science fiction, I found myself craving the mystery of the Gothic. This is an aesthetic preference only, not an aesthetic judgment, but a lot of what I read this summer left me cold, like the Creature on his ice raft, sailing into the darkness.

What did I read/watch? Emphatically not a list of recs

Here’s the science fiction I read and watched this summer:

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979) by Douglas Adams — fine, didn’t hate it

Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams (1987) — pretty good

Dark Matter (2016) by Blake Crouch — as my former landlord said about butt wipes, “no, no, no, NO!!!”

Project Hail Mary (2021) by Andy Weir — fine

Ender’s Game (1985) by Orson Scott Card — honestly, not my favorite

The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) by Ursula K. Le Guin — I didn’t even finish this, and before you ask, yes I am very ashamed (but also I didn’t like it)

Ready Player One (2011) by Ernest Cline — I liked this one! but in the barely-have-to-pay-attention-while-reading kind of way

Arrival (2016) directed by Denis Villeneuve — loved it, probably my favorite of everything on this list

Dune (2021) and Dune: Part Two (2024) directed by Denis Villeneuve — solid

As you can see, my reading was largely a bust. The watching was better. So where does that leave me? One word: Murderbot.

What do I actually recommend?

In the end, it turns out I prefer the science fiction I had already read: Frankenstein (obviously) and The Murderbot Diaries.

A couple years ago, my friend Edward brought a slim book to my house: All Systems Red (2017) by Martha Wells. “It’s about a depressed robot who is obsessed with television,” he said. “I think you’ll like it.”

And here’s the thing, I loved it. Living in a corporate space dystopia, Murderbot (they/them) is an android owned and operated by The Company. Except, they’re not operated by The Company because they hacked their system and set themselves free. Now they’re on the run from The Company, but, against their better judgment, they keep helping humans out and saving their lives, even though humans really annoy them and they’d rather be watching their favorite show, Sanctuary Moon.

Like Frankenstein, or Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (aka Blade Runner), Murderbot questions our long-held certainty that humans are distinct from other creatures and wrestles with the ethics of treating androids as subhuman. In that way, Mary Shelley was prescient and Martha Wells is timely, since we now live in an age when — to quote Washington and Lee University’s official policy — “AI is too broad to be ignored” (lol thank you W&L for that startling insight). It’s not sentient yet, but what will we do when it is?

I don’t know the answer to that question, but I do know that Murderbot has everything you want: it’s thrilling, it’s funny, it’s heartfelt, and — best of all — there are eight books in the series! It will keep you busy until our AI overlords seize power. And by then there won’t be anything you can do about it, except, perhaps, watch Sanctuary Moon.

Do you have thoughts about where I went wrong with sci-fi? Please let me know! I’m aware that a sample size of 10 is not a particularly strong basis on which to judge an entire genre.

Why did I do this? Well, I was under the significant misapprehension that I needed to understand quantum physics in order to appreciate science fiction. Good thing I was wrong because I do not understand quantum physics.

This, admittedly, is a reactionary stance. I am generally annoyed by the way our cultural preference for the rational has led us to trivialize anything perceived as irrational, mysterious, or superstitious (for instance, colonized people; also women). This dynamic is easy to perceive in attitudes toward literary genres, as well: realism, an ostensibly rational genre, is hailed as high art, while the gothic is “frantic, sickly, and stupid” (to quote William Wordsworth).

Obligatory caveat that I believe in climate change, science, and vaccines, and I do not support sawing off whale heads and strapping them to the top of your car.

From the author’s note in The Left Hand of Darkness (originally published 1969, author’s note 1976).

Shelley is vague about the details. Victor’s process involves both contemporary science and quite a bit of alchemy. But at the crucial moment when the creature is brought to life, Victor says: “I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

Or maybe it had been born over a century earlier with Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World. Either way, seems like a woman invented it.

Max Horkheimer writes that the end result of reason is “an empty nature degraded to mere material, mere stuff to be dominated, without any other purpose than that of this very domination.” From Eclipse of Reason (1947), but I found this quotation in Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences (Chicago University Press, 2017), 9.

I’ve enjoyed reading countless science fiction books since I was a teen, fascinated by the depiction of future societies, technologies and ecologies.

I haven’t seen the movie “Dune”, but thought the book was excellent. FWIW, here’s a list of other works that stand out in my memory:

Walter M. Miller, Jr.

A Canticle for Leibowitz

John Brunner

Shockwave Rider

Stand on Zanzibar

William Gibson

Neuromancer

Neal Stephenson

Cryptonomicon

SeveNeves

Mary Doria Russell

The Sparrow

I’m looking forward to reading Murderbot!

Oh man, loved this!

Have you seen "Her"? I feel like it holds those questions of both mystery-in-sci-fi and the human-AI relationship in interesting ways. (As an added delight, I also heard an interview with Spike Jonze where he said the main aesthetic inspiration for their futuristic costume design was Orange Julius.)

And ready whenever you are to form our local band, Galvani and His Frogs.