Friends! It’s been too long. I’ve been working on some other pieces for Night Hag — stay tuned — but in the meantime here are some book recs just in time for summer.

Since finishing Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, I’ve read three more historical novels. But not the boring Girl With a Pearl Earring kind.1 The whimsical kind! The fantastical kind! The OMFG-why-is-that-scorpion-so-big-and-IS-IT-TALKING-TO-ME?? kind.

Perhaps you think a talking scorpion in a historical novel sounds paradoxical. Perhaps that is too much fantasy for your taste. Well, never fear! I’ve got something for everyone, ranging from whimsical realism to, you know, the talking scorpion.

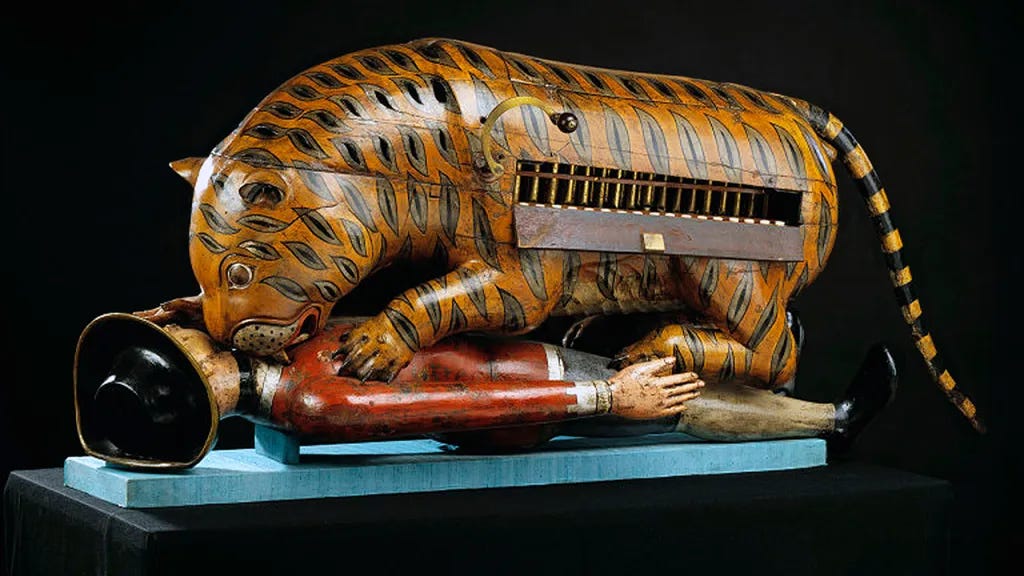

If you want no fantasy in your historical novel, you might like Loot (2023) by Tania James. Did you know there was a craze for automata in the 18th century? Mechanical men playing chess, women playing harpsichords, and defecating ducks delighted audiences across Europe. But in the Kingdom of Mysore (South India) in the 1790s, one particularly memorable automaton — a tiger eating a British soldier — delivered both thrills and chills, amazing Tipu Sultan’s subjects and implicitly threatening his English enemies.

Tipu’s Tiger is very much real (and on display at the V&A), but Loot is the fictional story of the people who made it. We follow teenage Abbas, a talented toymaker plucked from his father’s workshop and instructed to assist the royal clockmaker, Lucien, in building the mechanical tiger. During their work together, Abbas becomes fascinated by horology (clockmaking), and Lucien agrees to take him on as an apprentice. But there’s one problem: after many years in Mysore, Lucien is desperate to return to France. He sails for Rouen and tells Abbas to join him as soon as he can.

By the time Abbas departs for France, the journey is longer and more complicated than he anticipated. Loot is not a long book (300 pages), but it covers a lot of ground, tracking Abbas from Mysore to France to England as he tries to find Lucien and fulfill his destiny. The story culminates in an elaborate attempted heist (heists galore in today’s recommendations!) and…that’s all I’ll say about that.

One of the best things about Loot is how it interweaves Abbas’s story with the larger historical context: specifically, a moment when the British were violently expanding their presence in India.2 I love that James imagines this story from a Mysorean point of view, challenging British narratives of benevolent colonialism3 and making it clear how closely empire is linked to exploitation (or, if you like…loot).

Want to know more about British colonialism and loot? Check out this New Yorker article about the British Museum’s collection — itself comprised of many stolen or dubiously acquired treasures — and how it was recently looted by one of their own curators. Art heist!

If you want just a little splash of fantasy in your historical novel, you might like Babel (2022) by R. F. Kuang, which takes place in a lightly fictionalized 19th-century Oxford. The premise: at the heart of Oxford lies a highly-selective language institute called Babel. And Babel is not just a place of learning: some kind of magic is happening inside Babel’s well-fortified tower, and this magic is essential to the rapidly expanding British empire.

In many ways, Babel is a version of the 19th-century orphan novel (or bildungsroman, if you want to be pretentious about it) — think Great Expectations (1860–1), Oliver Twist (1837–9), or Jane Eyre (1847). But Kuang reimagines this genre by placing the question of empire at the center of the book (which Dickens and Brontë simply don’t do).4 Our protagonist is Robin Swift, a Cantonese boy who is taken from his home and brought to England at a young age. Like Pip or Jane, Robin finds himself virtually alone and trying to navigate a world he doesn’t fully understand. The outsider is a useful tool for the novelist: a figure that allows readers to look at a familiar world in a new way, perhaps challenging some of what we take for granted about that world. In Great Expectations or Jane Eyre, it’s the social milieu that we see from the outside; but in Babel, it’s all of England. And as the novel progresses, Kuang leverages Robin’s outsider perspective — and that of the friends he makes at Oxford — to call into question 19th-century Britain’s fundamental assumptions about itself, especially the idea that the “progress” of empire is worth all the pain, suffering, and exploitation.

Eventually, of course, Robin becomes a student at Oxford — at Babel, to be precise — and the real intrigue begins. He interrupts a theft (a heist?) in the dark of night! He’s recruited into a secret society! He learns to do (some) magic! At first, the picture of Oxford is just as rosy as you might expect; but as the novel unfolds Robin becomes more and more disillusioned. How to describe this book? Sort of Great Expectations meets The Secret History crossed with an astonishingly erudite dissertation about colonialism and translation? Add a dash of campus protest and voila! you have Babel.

Kuang is incredibly knowledgeable about 18th- and 19th-century literature, history, and politics, and that knowledge is on full display throughout the 500-page novel. I sometimes found this aspect of the book a bit tedious, but I think it’s important to the task of revision that she so successfully executes here: revising the 19th-century novel, revising stories about Britain and the British empire, and — perhaps most shocking to the Harry-Potter-pilled American student — revising representations of Oxford itself.

I guess I should say “Dark Academia…blah blah blah.” Did I do this book justice? I don’t know. Read it and let me know what you think!

Finally, in the category of Wow What a Wild Ride, we have: The Adventures of Amina Al-Sirafi (2023) by Shannon Chakraborty. This book is nuts. But in a fun way!

Set in and around the Indian Ocean in the 12th century, the book features an unusual protagonist: a middle-aged woman pirate, Amina, living a quiet life with her daughter and mother. As a pirate, Amina was legendary — so legendary that her name is the stuff of songs and tall tales. But in retirement, Amina is trying to keep a low profile — she might have been a little too good at her job, and she fears retribution from her many enemies.

One day, however, a wealthy old woman shows up at Amina’s door and asks her to take one last job: rescue the woman’s granddaughter and walk away with an enormous amount of money. Should she take it? Probably not. But the woman isn’t taking no for an answer; and besides, Amina misses her beloved ship.

This is when things really start to pop off. Dangerous wizards, sexy chaos demons, terrifying and truly enormous sea monsters…need I say more? You know how an adventure story goes. Imagine the Odyssey plus 1001 Nights, but make it much more historically and culturally specific, and then update everything with LGBTQ+ characters and sex positivity and I think you’ve got it!

I loved this book for many reasons, but partly because it’s so well-researched. As with Loot and Babel, it’s evident that Chakraborty put a lot of work into bringing the historical world of the novel to life. This may seem like an oxymoron, given that much of the book is so flamboyantly fictional, but Chakraborty does a great job balancing the real and the imagined. I felt immersed in Amina’s daily life one moment and flung into the realm of fantasy the next.

Well, everyone, that’s all for today. Hope you enjoy and see you soon!

What do I have against Girl With a Pearl Earring? I don’t know. Maybe the fact that I was forced to teach it to a classroom full of 9th graders. But for some reason it’s just what comes to mind when I think of historical-novel-as-restrained-period-piece. Unless…omg remember Ann Rinaldi? That book about Benedict Arnold shook me.

At this point, British rule of India was via the British East India Company, which was founded in 1600 and rapidly expanded in the 18th century. Although it was a trading company, the British East India Company operated more like a government: using private armies to conquer, control, and tax large areas of India. Direct rule of India by the British Crown would not begin until 1858.

In case you’re thinking, who believes that colonialism is benevolent?, let me tell you: the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World refers to the British East India Company as “a benevolent enterprise.” Okay, but that book was published in like 1950, right? Nope. 2008.

Empire is often present in 19th-century novels, but in the background. In Austen’s Mansfield Park (1813), for example, Sir Thomas Bertram travels to his plantations in the Caribbean, but the story doesn’t follow him there (in fact it’s barely mentioned). Brontë’s Jane Eyre, too, has a whole backstory that takes place in the Caribbean (Bertha is born there and the text not very subtly suggests that this is the source of her corruption); but again, the colonies and the question of empire/enslavement are not foregrounded in the novel.

103rd in line for the Adventurs of Amina Al--Sirafi over here!

I’ve put in a library request for “Babel”. It’s popular here - 14 people are ahead of me, with just a dozen copies on order. The other two books sound fascinating as well!