This essay is about weirdness — a close relative of the spooky, but not exactly Gothic. The recs below may scratch some of that Spooky Season itch, but if you’re already sipping your pumpkin spice and need something a little more Halloweeny to keep you company, check out my guide to Night Hag recs, as well as my posts on haunted houses, witches, and general Gothic vibes.

Lexington, David Lynch, and MAGA

In recent years, I have had a strange response to the High Americana of summer. Among the picnic tables, burgers, and bikinis, I find myself searching for the weird. I develop an odd desire to read about aliens. I start wondering about the seedy underbelly of my beautiful surroundings. For all of this I blame David Lynch.

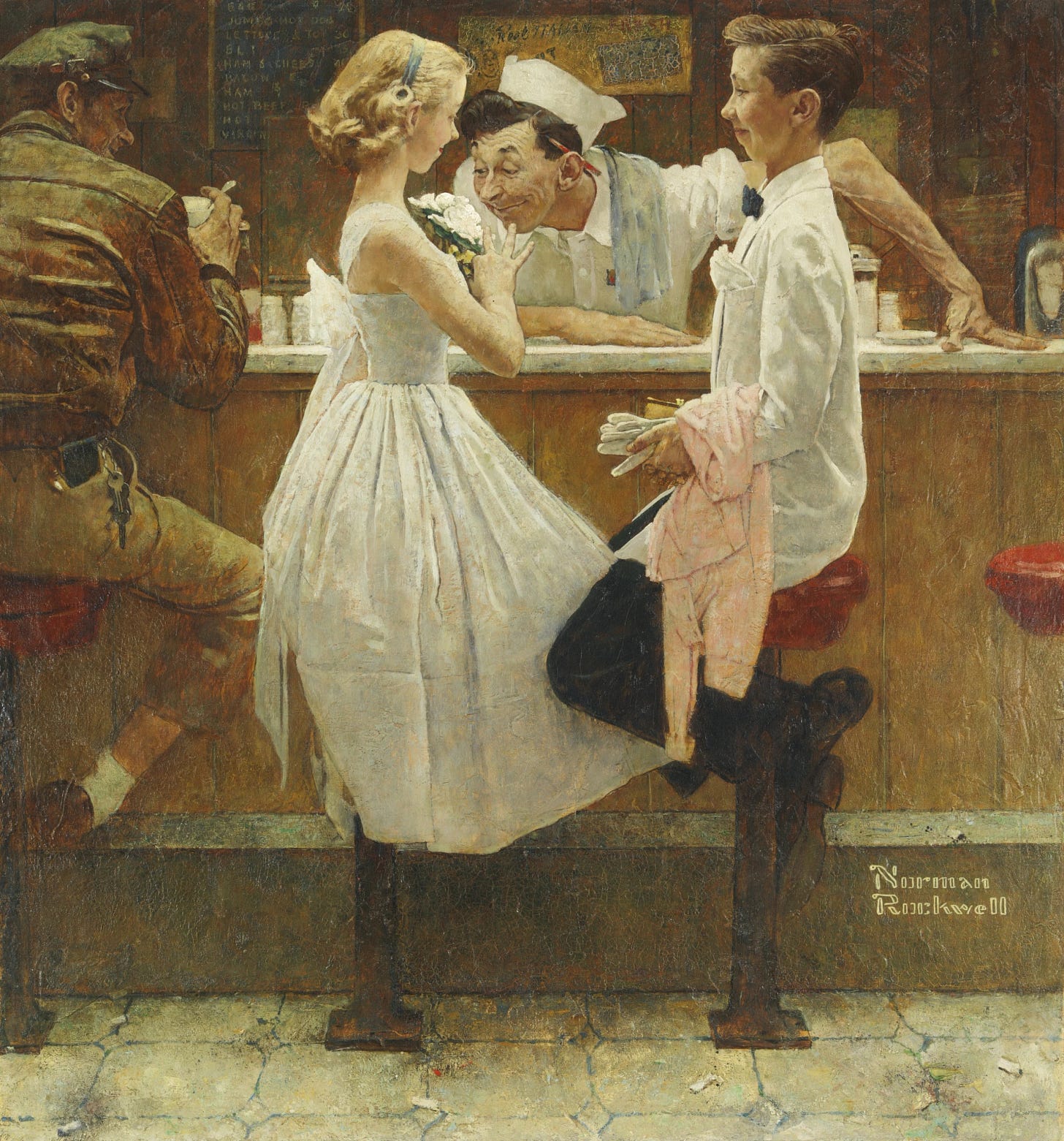

Eight years ago I moved to Lexington, Virginia, a tiny town in the Shenandoah Valley that was once described to me as “like living in a Norman Rockwell painting.” In many ways, this is accurate. The kids here still walk to school on their own. Matthew and I have a charming 13-year-old neighbor who mows our lawn for $30 when he’s not riding his bike around town. We went to a high school football game last week. You get the idea.

But is living in a Norman Rockwell painting a desirable thing? You could say that this is the question posed not only by Lexington, but also by David Lynch and by our nine-year MAGA moment.

Historic Downtown Lexington evokes a bygone era of American life. But here, as in much of the southern United States, a bygone era doesn’t just mean gorgeous Neoclassical architecture: it also means close ties to slavery and the people who fought to protect it. Lexington is the home of Washington and Lee University, which is named for General Robert E. Lee.1 Both Lee and Stonewall Jackson are buried in town, and people regularly make pilgrimages to their graves. I love it here — it is incredibly beautiful — but you don’t have to look far beneath the surface to sense that something is not right.

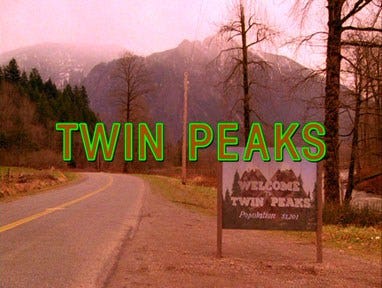

This is the same feeling created by so much of David Lynch’s work, especially Twin Peaks (1990–1) and Blue Velvet (1986). Lynchian scenes are full of white picket fences, 1950s diners, and All-American boys next door, but you quickly realize that this veneer of wholesomeness covers something much, much darker. In this way, Lynch is a master of the uncanny: he’s very good at taking iconic images of “traditional” American life and making them uncomfortably strange.

The same, of course, could be said for MAGA (except they’re not doing it deliberately). Trump & friends have always conjured some fictional version of a 1950s past,2 but they seem to become more explicit about wanting to move America backward every day, with the Supreme Court overturning Roe and Vance calling for women to be back in the home where they belong (to name only two examples). Like the villain in Twin Peaks, Trump and Vance are selling you something that they desperately want to be seen as wholesome, but which is in fact deeply sinister.3

So, back to the question at hand: what has pushed me into my now-intense love of the weird? Quite simply, Lexington: I live in Confederate Twin Peaks. On the surface it’s all small-town charm, but there’s a sense that the Generals are not what they seem. (Or maybe they’re exactly what they seem, and that’s the problem.)

But in a broader sense perhaps we’re all living in Twin Peaks. The last nine years have made us paranoid and suspicious; it’s not so easy to accept people at face value anymore. We walk around wondering can I trust that you are what you appear to be? Do we share the same set of facts? Do we live in the same world? DID YOU KILL LAURA PALMER??? Life is…weird.4

So, what is the weird?

Weird fiction shares with the Gothic a strong sense of the uncanny, the eerie, and the strange. But while Gothic literature tends to be recognizable by certain conventions (vestiges of the past, haunted houses, tyrannical patriarchs, dark and gloomy settings, etc.), weird fiction is primarily characterized by atmosphere. According to the patron saint of weird, H.P. Lovecraft, “atmosphere is the all-important thing”:

The one test of the really weird is simply this — whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.5

A profound sense of dread, you say? That sounds so familiar, where could I have felt that recently…oh that’s right, I almost forgot: every time I look at the news for the past nine years. What a time to be alive!

The word “weird” has appeared quite a bit in the culture recently; it might be second only to “brat” as the word of the summer. Tim Walz, Kamala Harris, and the Democrats have used “weird” to describe Trump & Vance and their vision for the United States. But is their weird the same as Lovecraft’s?

When Walz, Harris, et al. say “weird” they mean something like, “out of step with the American mainstream.” They intend to highlight the fact that Trump & Vance plan to implement policies — like extreme abortion restrictions, for instance — that are not broadly popular. Trump & Vance are niche. They are weird.

It is certainly true that Trump & Vance cause me to feel a profound sense of dread, but when Lovecraft talks about the weird, he means something far stranger than Trump & Vance. For all the horror of their policies, Trump & Vance are, themselves, depressingly familiar. To lightly paraphrase Kamala, they are the same, tired patriarchs that we’ve seen trying to dominate and control everyone around them throughout American history. In my opinion, they don’t deserve the distinction that weird confers. They are so depressingly literal. So wearyingly explicit. So boringly normative.

Um…you said you had some recs?

But you know what isn’t boringly normative? The four weird recommendations I have for you!

Obviously the best case scenario would be that you’ve never seen Twin Peaks and you get to watch it for the first time. (What I wouldn’t give.) What I love about David Lynch is the surreal, often unexplained quality of his work, and his expert juxtaposition of the familiar with the bizarre. You’ll get plenty of that in Twin Peaks, plus a damn fine cup of coffee!

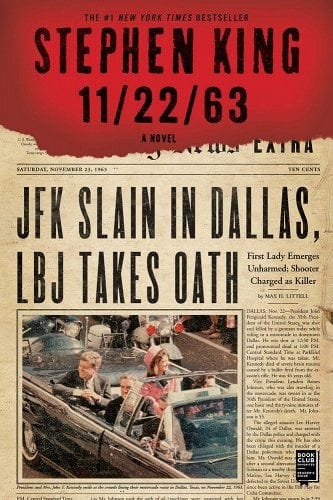

11/22/63 (2011) by Stephen King. This book imagines: what if you could go back in time and stop the JFK assassination? A 21st-century man travels back to 1958: he has five years to find Lee Harvey Oswald, determine if he really did kill JFK, and then stop him before he does it. I don’t know if this would count as true “weird fiction,” but it certainly has weird elements, and it fits nicely with the broader theme of this newsletter: an uncanny — although occasionally nostalgic — depiction of the American past, suffused with a feeling of dread. I devoured this book this summer, all 880 pages of it.

Welcome to Night Vale (2015) by Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor. This is more of a progressive-desert flavor of Americana (ooooh I would totally order Progressive Desert at Salt & Straw), and it is deeply strange in the best way. But! Please trust me when I say that it is absolutely absurd and you need to have a high tolerance for absurdity in order to enjoy it. Based on, but not the same as, the podcast of the same name.

Finally, would you like an Australian version of the weird? Perhaps you would enjoy Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967) by Joan Lindsay. Set at a girls’ boarding school in early 1900s Australia, this is the story of three girls who go missing during an outing to, you guessed it, Hanging Rock. It is so weird in the best way, the mystery so strange, the atmosphere of dread so thick. I love this book (and there’s a great movie, too). As a bonus, if you want to have your mystery explained, there’s an unpublished final chapter — written by Lindsay herself — that tells you what happened. But you can also just enjoy it as it is: a very weird book about three girls who disappear and the way their disappearance affects the community.

That’s it for this week! Stay weird, everyone.

Lee was president of Washington and Lee (then called Washington College) from 1865–70.

Rockwell’s version of the past is also fictional; but whereas Trump and Vance would claim to return us to something that really was, Rockwell was upfront about his paintings being romanticized: “Rockwell would have been the first to tell you that the pictures he painted were not meant to be taken as a documentary history of American life during his time on earth, and least of all as a record of his life. He was a realist in technique, but not in ethos. ‘The view of life I communicate in my pictures excludes the sordid and ugly. I paint life as I would like it to be,’ he wrote in 1960, in his book My Adventures as an Illustrator. To miss this distinction, to take Rockwell’s paintings absolutely literally as ‘America the way it was,’ is as misbegotten as taking the Bible absolutely literally” (from Vanity Fair).

Trump and MAGA may have made Americana scary again, but the Southern Gothic has explored the sinister side of the US for a long time. As Sheri-Marie Harrison writes: “In American literature, there is a long tradition of using Gothic tropes to reveal how ideologies of American exceptionalism rely on repressing the nation’s history of slavery, racism, and patriarchy. Such tropes are, as numerous critics have noted, central to the work of Toni Morrison.”

Naomi Klein has written brilliantly about the uncanny quality of the Trump era in her book Doppelganger (2023), which I highly recommend.

H.P Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927).

I haven't seen Twin Peaks or Blue Velvet. I guess I'm just more of a reader than a watcher. t am looking forward to reading Welcome to Night Vale,. I appreciated your commentaries on Lexington and Norman Rockwell - very interesting and informative. Thanks!

Love this. Just when I wondered "But what about Walz..." you were like "I know, I know."

Relieved and glad that we can still claim weird.